As some of you know, I write an occasional column for McSweeney's Internet Tendency, "Speaking for all Christians Exactly Like Me." The column came about as a result of McSweeney's annual contest, which awards ten or so people with an opportunity to write for the site for a year. Today, I'm continuing an ongoing series of interviews with the other nine winners (or as many of them as I can track down and get to return my emails).

Today’s guest is KA Semenova, author of the McSweeney's column "Classic Russian Writers: For teh Internets." You'll probably figure this out on your own, but my questions and responses are in italics.

JJ: So, I want to start with asking you a little bit about your column and the theory that lurks behind it. You say in your bio that you want to test the “theory that human nature is neither analog or digital,” so you “update classics of Russian literature with modern technologies to see if the insights of those writers hold up today.” Can you expand on what you mean when you say you "update" a story for teh internets? Beyond the different technology, is there a sense in which you're trying to "update" the themes of the story too? Or is that one the points you're trying to make, that there are certain meanings that endure in spite of technological change?

KA: Yes, to your last sentence. I’m not trying to update the theme of the story at all. My entire point is that updating the technology does not change the meaning of the story, in any fundamental way. Why would it?

My sort of ongoing thesis—or my hobby horse, if you know me—is that human beings are more alike than they are different. I think that is true across cultures as well as across time. Which means, in this context, that human beings are human beings, whether they are using a teletype machine or texting. And that’s what this little experiment is all about.

If I can trace the origin of the McSweeney’s column to one thing, I’d say it’s this: I belong to some writers’ groups on Facebook, and once this guy, let’s call him Bob, asked for recommendations for novels that dealt with infidelity, to see how other writers had handled it. And I suggested that Bob read Anna Karenina, because Tolstoy had covered that particular ground, and had done it brilliantly.

And Bob said back to me, “Why would I read something that old? The world is so different now, how could I possibly find that useful?”

And I think that is just about the dumbest thing anyone has ever said. And I find it particularly distressing that it comes from someone who calls himself a writer. He epitomizes for me a kind of narcissism, a solipsism out there—that you see often on the Internet—that “our world” is fundamentally different than the world that came before.

I just don’t think that’s true, and my McSweeney’s project is about playing with that idea, doing case studies, as it were. What happens when you put a Chekhov character on Twitter? Is he still the same person? My revision of “Lady with a Dog” suggests that Gurov and @Gurov are exactly the same guy.

JJ: So, breaking in here, with this in mind, what do you think about science fiction? Because some science fiction writers would say that the advancing technology portrayed in their stories does alter their characters in fundamental ways. Actually, this is a pretty common definition of science fiction, a story in which the science is so important that it cannot be removed or changed without fundamentally altering the story. It's really hard to take something like Neuromancer, replace the technology, and still understand who Case is as a character. Though it's really easy with something like Star Wars, which is a fantasy story pretending to be science fiction.

I guess I'm wondering if we could reverse the process you do, like take a science fiction story, replace the technology with something more primitive, and see if the story still made sense. Maybe it depends on the technology; perhaps the Internet doesn't fundamentally change things in the way that, say, true artificial intelligence would.

KA: Interesting question. But I’m not sure I have a great response because I don’t read science fiction. It just doesn't interest me because, in my mind, I already know the answer to the question, and the answer is that the technology is largely irrelevant. Science fiction, however you slice it up, is about human relationships. Those books are genre—they’re quests, or romance novels, or war novels, or what-have-you—dressed up in a different world.

And I can sort of understand, theoretically, that it would be interesting to play with the laws of physics, etc., but personally, it doesn't draw me in. So I can’t respond here with any good examples because I haven’t read anything resembling sci-fi since I read God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater in like 8th grade.

But I will give you this to think about: Historically, UFOs anticipate the next development in technology. Meaning, if you go back to 18th century Europe, the UFO reports are big steel ships in the sky. In the 19th century, reports are about plane-shaped objects. In the last century, they became flying saucers. So it seems to be a fundamental part of human nature to see UFOs, but their descriptions change over time; so clearly there is a relationship to technology as it evolves. Humans apparently always anticipate (and fear) what technology will bring next.

And I think that might bring us to Jonathan Franzen, yes? I mentioned him in my McSweeney’s bio as one of the catalysts for my project.

About a month before I wrote the first column, Franzen published a screed about the Internet and technology and culture more generally. The article really amounted to a big fat nothing. He constructed a straw man (he clearly doesn't understand Internet culture at all), then utterly failed to destroy it anyway. And I think that’s too bad. There was a moment that I really liked Franzen, in the 90s, when I read The Corrections, and when he refused the Oprah’s book club imprimatur, which I thought was interesting. I sort of got him about that, and thought he had something useful to say there.

And ever since (I realized when I saw his last piece), I've been waiting for him to say something interesting, do something usefully provocative, but he’s not delivering. Somebody said, about this last piece, that he’d become an old man yelling at kids to get off his lawn. Exactly.

So I referred to him in my bio because, like him, there are certain things about the Internet that bug me. I have questions about the way technology might be changing us. But I’m more interested in nuanced discussion, in asking questions, which Franzen isn't doing. He’s rather offering up opinion in the form of verbs, like saying Rushdie “succumbed” to Twitter, as if it were a disease. That doesn't get us anywhere.

To me, Franzen is doing what Bob did, just in the opposite direction. Franzen likewise is positing fundamentally different pre- and post-Internet worlds, though in his case, he idealized the before, whereas Bob idealizes the now.

JJ: Do you think some familiarity with the original Russian stories (in translation or otherwise) you update is necessary to really appreciate what you're doing?

KA: Maybe. At least in the form they’re offered on McSweeney’s. John Warner and I have discussed this issue. In my original submission, the editing I did to the story was shown. The reader could see the red-lines and the replacements, so he or she could see very clearly that I only had to change a few words to bring Chekhov up to date in terms of technology and setting. But McSweeney’s had some technical problems displaying that, and John was also concerned that it interfered with the enjoyment of just reading the piece, which was also a concern of mine.

So we agreed to post them with all changes accepted, as it were. And that I would post the red-lined versions on my own website, so that anyone who is really interested can go look at the editing, to see what exactly I did.

But to respond to what I think is a kind of implicit question in your question—eg, does anybody besides you get what the hell you’re doing?—I don’t know. I know John does, obviously. Because we’ve talked about it. I do hear where I think you’re coming from, though, that there is inherently a somewhat limited audience for these pieces. But that’s really okay with me, because that is the great thing about the Internet, that you can find limited audiences, fellow Russian literature geeks like yourself. And there are a lot more of them out there than you’d think.

In any case, this is what I've always liked about McSweeney’s, that it is often like hanging out with a bunch of grad students, at a bar, after class. It can be a kind of para-academic, funny place. And I think—and I hope I don’t offend anyone, but—for much of McSweeney’s stuff, it’s not really about reading every word of every column. It’s about seeing the title, and reading a piece, and getting what the writer is doing, and considering that idea. And usually laughing. Part of the fun is whether you get the joke of it at all.

I’m totally a person who believes in tribes, and I know mine. So when John said to me, when I submitted a piece, “Amazing. I’d never heard of Karamzin. This is fascinating,” I knew that a tribe member had gotten what I was doing. And I felt like I’d just won the Internet, so it’s all good to me.

JJ: Grad students at a bar—that sounds about right. I remember when the column contest was in its judging phase, John tweeted something about how around 25% of the entries had PhDs and about 50% had advanced degrees of one kind or another.

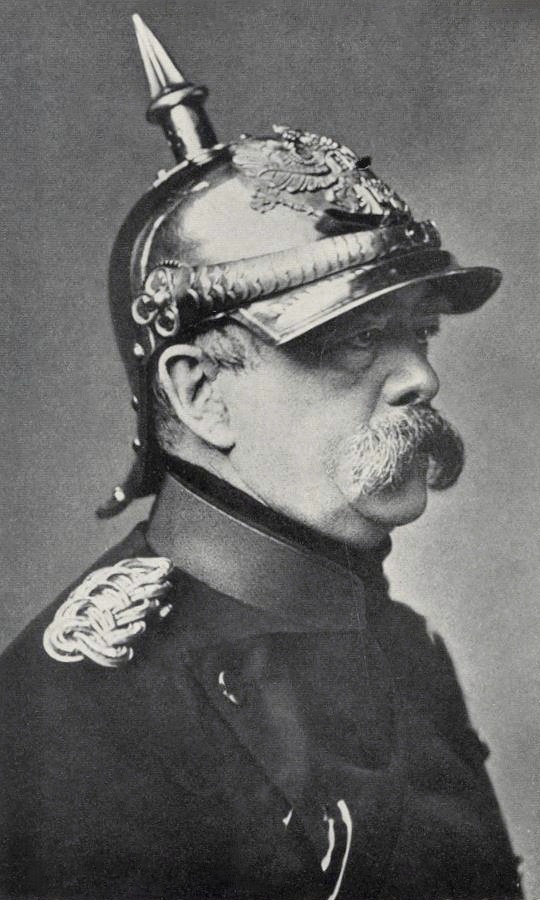

KA: That sounded exactly right to me too. I was in a history PhD program at Georgetown (left early), and one night a group of us sat around after class at the Tombs, a bar, constructing the funny hat theory of history. We almost killed ourselves laughing as we developed an outline. Even assigned chapters to each other. I was supposed to write on the pickelhaube. (picture right) Which of course I never did. Maybe I should reanimate the theory, and submit it to McSweeney’s next year.

Anyway, it’s kind of enough for me if someone notices that I put Gurov on Twitter, and then they think about that notion for a second, making of it what they will. My goal really is to raise questions, not answer them. Because, to return to Franzen, deciding the Internet is “bad,” just gets you nowhere: it gives you no answers, it gives you no questions. And to decide, like Bob, that writers before 2000 have nothing interesting to say is even worse. Both are intellectual dead ends.

JJ: How'd you get started writing? For a general audience, that is.

KA: I’m not sure I have yet, exactly. I’ve worked around publishing for about thirty years now, which is working with writing, but behind the scenes. Most of my writing for a long time was academic (I have an MA in Russian history) or things I did for myself, like journaling. I only started writing seriously, aiming for publication, about five years ago. (I have two novels in progress and two memoir-type things, too. I like to skip around!) And I didn’t really expect McSweeney’s to take my column, which meant I wasn’t quite prepared to go public yet. (Which is why I had to delay publishing this Q&A, because my web site wasn’t ready yet!) I always thought I’d go “public” later, with one of the long-form pieces.

JJ: Can you give us a little teaser on what these books are about?

The memoirs are about my Russian family, who lived the 20th century the way most Russians did—war, famine, emigration, etc. I’ve been engaged on a genealogical/historical research project involving them for twenty-some years now, so those books are about that. What I’m working on right now, though, is crime fiction, set in northern Ohio. Sophie, a PhD candidate in history who has been away for a decade, comes home to hole up in her grandmother’s cottage on Lake Erie to write her dissertation. When a priest at a nearby Russian Orthodox Church is murdered, Marty, her old high school boyfriend, who is now a sheriff’s deputy, asks for her help. Then another priest is murdered…

JJ: Is that the kind of thing you like to read too? What do you think is the best thing you’ve read recently?

KA: Hmmm. Without a doubt, Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. I spent the week between Christmas and New Year’s Eve with it—it’s an 800 page novel—and had the most fun I’ve had in years with a book. Couldn’t put it down. And just before that, I read Death of a Nightingale, Lene Kaaberbol & Agnete Friis’s third novel. More generally, for the last few years, that’s the kind of thing I’ve been reading: Scandinavian fiction, mostly the crime fiction, though not exclusively. (And this started for me long before Dragon Tattoo went big. I’d read all of Henning Mankell by the time Larsson broke out.)

There is something deeply interesting about what is going on with crime fiction in northern Europe, not only in the Scandinavian countries, but also people like Tana French in the UK. Right now, I’m reading a book by a Swede, Johann Theorin. I had to order two of his books from the UK—they’re not available in the States yet—because I just love his sense of place.

JJ: So you are a Scandinavian crime fiction hipster?

KA: Yes! I’m not ashamed to say it! I have a whole big theory about it, to tell you the truth. I think the Scandinavians are up to something very interesting. They are perhaps alone in genuinely taking on the way neoliberalism (and the fall of the Berlin Wall) has shaped our world over the last couple of decades. They are the people who are really grappling with this, in fiction, in my opinion.

Many people like to say that the crime novel originated in the UK (with Sherlock Holmes) but I think that’s just wrong. (Of course, it’s usually Brits who say this.) Some people point to Poe, in the States, working a few decades earlier, but again, I just don’t buy that. Poe wasn’t quite doing crime fiction, and I don’t think American crime fiction has ever been especially interesting, then or now, in terms of its ambitions. It tends to be genre, and while many of the Scandinavians are doing genre stuff, a lot of them are much more ambitious.

I think that crime fiction, of a certain kind, anyway, originated with Dostoevsky, and that some of the Scandinavians are up to the same thing he was doing, which is using crime fiction to comment on social reality. I’m so interested in this, in fact, that I want to do a blog on it. I’ve registered a domain, and I’ve got some posts ready, but OMG, so not enough time in the day…

JJ: That’s a type of fiction that I don’t think I will ever really appreciate, mostly because I can’t handle the creepiness of it, especially the books about serial killers. I’m much less afraid of supernatural monsters: demons, witches, vampires, whatever, which I think is mostly because I assume that those creatures all have rules that govern their behavior. Serial killers are a complete mystery to me; their motivations and actions make no sense. It’s similar in some ways to how I’m afraid of bees and wasps but not snakes or rats or birds. I know what a bird is going to do, but I can’t ever figure out what a bee is going to do.

KA: Wow. We’re so different. I don’t like reading something when I know what’s going to happen, for exactly the reasons you cite. If it’s a zombie, I know he’s going to walk around stiff-legged and try to eat brains. If it’s genre mystery, then the detective is going to get the bad guy in the end. Where’s the fun in that?

I like books in which the end cannot be predicted; or if it can be (like the Wallander books; which are conventional police procedurals in that sense), then there must be something else at stake. In that instance, it’s Wallander’s health and relationships; but also more broadly, the health and relationships of Sweden, as he’s taking on political changes in the world and how that’s affecting the country.

JJ: So if zombies or vampires or demons don't scare you, what does scare you? Anything?

KA: Bad dreams. I had one recently. I woke up at 4:25 am, with my heart pounding, and I didn’t know where I was. I looked around my room, and it took me a long time—like a minute, no joke—to be sure I was home, in my bedroom. Because I’m not usually up at that time, of course, so the light was kind of odd and things looked different, somehow.

And in my dream, someone who I have seen exactly once since 1983 had just gotten hit by a bunch of falling metal boxes. (I have no idea where they came from.) He was leading me out a door, then the boxes fell, then he was lying on the ground, with a bloody face, and I was frozen, trying to call 911. Which is the moment I woke up.

I don’t have bad dreams like this very often, like maybe once every five years or so. But when I do, they’re really awful. I don’t tend to be prophetic on this score, thank God. I have no idea what triggers them. Wish I knew. I’d stop doing whatever it is.

JJ: I have attempted to hurt my wife three times in my sleep, twice I tried to choke her, once I punched her really hard. All three times I was having a dream where I was protecting her from some kind of attacker. So I have this fear of doing really serious harm to her in my sleep, which is sort of related to a larger, general fear of hurting the people I love, which probably has something to do with my fear of my own brain, and how weird it can get sometimes in there.

KA: Wow. That’s horrible. I’m so sorry. I get how freaky that would be. Though you’ve oddly made me feel better, I must say. At least I don’t have to worry about hitting someone.

JJ: Glad I could help. Let's end on a hypothetical. Suppose that somebody you loved was going to enter the McSweeney's column contest next year. What advice would you give them?

KA: I would say to them, “If you do it, what’s the worst that can happen?” And if the only answer they can come up with is “They’ll say ‘no,” then I’d say, “As worsts go, that’s not much.”

Because that’s how I got myself to do it. In fact, I adopted “What’s the worst that can happen?” as my mantra, the question to ask myself when I’m unsure about whether I should do something, take a chance. Over the last year or so, it’s got me a McSweeney’s column, a distressed turquoise chalk-painted bookshelf, and a new kitten. And I’ll be teaching a workshop in Puerto Rico in August. So I’d have to say this mantra is really working for me, so far.

You can read all of "Classic Russian Writers: For teh Internets" at McSweeney's Internet Tendency. I'd suggest Vsevolod M. Garshin's "The Signal." That one is a killer.